Lost in Translation: The case of Chinese

Mandarin Chinese constitutes the official and most widespread spoken dialect of the People’s Republic of China; it’s the official language of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and one of the four official languages of Singapore, while its writing system is also used by speakers of other Chinese dialects. It belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family. The Chinese language is of particular interest not only because of its rich cultural heritage, but also thanks to its special attributes. Let us explore some of these attributes that make Chinese such a unique language:

- It is a tonal language: it has 4 tones as well as a neutral tone and the meaning of each word is not determined by its constitutive elements, but by the intensity of the tone and by the position of the word in question in the sentence (syntax).

- It has a very large number of words that sound the same because the language has very few sounds thus amounting to words with similar accent, but different meaning.

- The Chinese language has no alphabet; it consists of characters-words (approximately 50,000), that is to say symbols that represent meanings and not syllables or speech sounds.

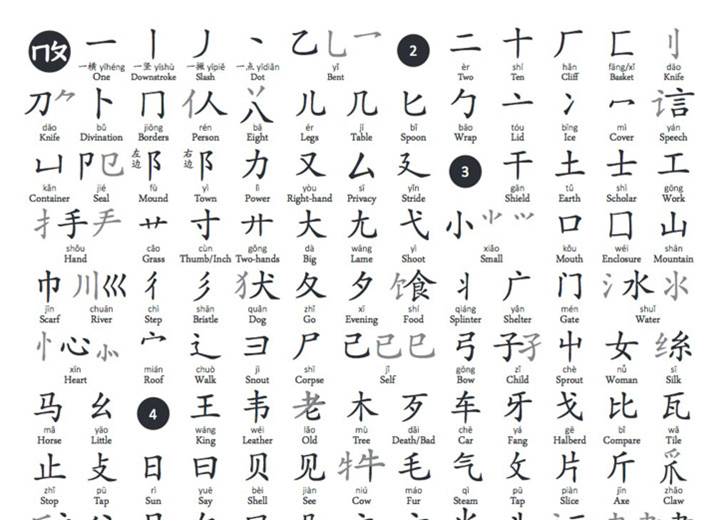

- Most characters consist of semantic radicals, which are basic non-autonomous characters that help enrich concepts and characters and improve the meaning of the basic characters.

- It is a language that does not use gender, singular or plural, verb conjugations and spelling rules; it is based solely on character interpretation

Next we will see how these attributes impose a different mindset on the speakers of the language and how this different way of thinking is eventually “lost in translation”. Translations of Chinese texts often deprive us of the exact meaning behind the visual representation of characters. Such an example would be case of radicals explained above. Radicals are grouped depending on the number of “strokes” required for their writing.

Examples of radicals:

好 hǎo = Well, good, very,

Suffix denoting the completion of an action

Adjective, attribute, adverb

女 (woman) + 子 (child) [radicals]

A woman with a child denotes completion; it is a joyful event leading to the creation of a family unit.

国 guó= country

囗 (borders) + 玉 (greenstone), symbol of king and power

The Chinese saw greenstone as a “royal gem” and in their long history of art and culture, greenstone assumed a very important role, acquiring similar value as that of gold and diamonds in the West.

In the above mentioned examples we can see that the meaning of the radicals is not transferred in the target language through the process of translation.

Absence of Verb Tenses

Although verbs in Chinese are an important part of the sentence, their form remains unchanged, unlike verbs in Indo-European languages. The verbal form of verbs coincides with that of the first person singular present tense, which remains unchanged. Chinese speakers do not divide time in the same way as other languages force us to do in order to speak correctly. When we talk about the future we are “grammatically” forced to separate it from the present and face it as something structurally different. Thus, we end up slightly disconnecting the future from the present. In this way, the future is considered as something distant and different from the present. This is not the case in Chinese.

Example:

昨天下雨 (zuótiān xià yŭ) it rains yesterday

现在下雨 (xiànzài xià yŭ) it rains now

明天下雨 (míngtiān xià yŭ) it rains tomorrow

Cultural Elements

- Family relationships – Terms of address

Terms of address in the Chinese language vary depending on age, gender, side (father/mother), and kinship (by blood/by marriage). In China, family and family ties are considered very important. In the past, families consisted of many members and hierarchy played an important role and had to be respected. The members of family, depending on their place and age, were not allowed to call their seniors by their name. This is reflected in the variety and differentiation of terms of address in the Chinese family. Each member has his/her own special title. Most of these titles of address are not used anymore as the hierarchy rules are considerably looser nowadays because of the one child policy implementation and the consequent reduction of family size.

Examples:

Uncle

– father’s older brother (伯伯 – bó bo)

– father’s younger brother ( 叔叔 – shū shu)

– father’s sister’s spouse ( 姑父 – gū fu)

– mother’s brother ( 舅舅 – jiù jiu)

– mother’s sister’s spouse ( 姨父 – yí fu)

Aunt

-father’s sister (姑姑 – gū gu)

– father’s older brother’s spouse (伯母 – bó mǔ)

– father’s younger brother’s spouse ( 婶婶 – shěn shen)

– mother’s sister ( 姨妈 – yí mā)

– mother’s brother’s spouse (舅妈 – jiù ma)

As we can see, there are five different names for “uncle” and “aunt” respectively, while based on the same logic, there are also different names for one’s brothers, cousins, grandfather and grandmother.

- Concepts of particular cultural significance

Examples:

关系 (guānxì – forming of relationships)

A word and concept you will encounter very often in China. Guanxi refers to personal influence and network development, which is the key to making deals in China, opening up doors to the entrepreneurial world and trade.

丢脸 (diūliǎn – lose face)

It literally means “to lose face”. Feel dishonoured/ embarrassed/ be exposed, humiliated/lose one’s pride. Chinese people believe that the face is a reflection of the spirit and if someone “loses face”, their spirit is lost along with the face. It is worth mentioning that the English phrase “to lose face” is a Chinese loan.

- Dietary Habits

Examples:

火锅 (huŏ guŏ – literally: pot on fire)

Finely sliced vegetables and different kinds of meat are dipped briefly in a boiling broth, in a pot usually divided in two (spicy and non spicy broth) on a dining table. The consumption of this particular dish can take up to hours as it is seen as a whole ritual. There is even a special verb (涮:shuàn) Chinese people use to describe the movement one makes with the chopsticks in order to cook the ingredients.

皮蛋 (pídàn – literally: egg with skin)

“Century eggs” or “thousand-year-old eggs” are a well known Chinese delicacy made of duck, chicken or quail eggs which are preserved in a special paste for several weeks or even months.

The dark green colour of the egg yolk and the egg white turned brown make the eggs look indeed “thousand years old”, although they are only a few months old. Century eggs are eaten plain or as an appetizer and are sometimes added as a main ingredient to several main dishes. The “skin” part refers to the special paste they’re preserved in.

蚂蚁上树 (mǎ yǐ shàng shù – literally: ants climbing a tree)

The dish consists of ground pork cooked in a spicy sauce and poured over bean thread noodles and it is a classic Sichuan dish. Its name implies a great sense of humour and a great deal of imagination: the bits of ground meat clinging to the noodles evoke an image of ants walking on twigs.

It is a well-known fact that the amount of Chinese texts translated to other western languages is very small compared to translations from other languages to Chinese. And this can be easily explained since transferring the exact meaning of a Chinese text to other languages is a true challenge. The examples explained above bear witness to the importance of intercultural communication in the translation process. Familiarity with the cultural characteristics of the two languages is a necessary condition for Chinese translation, and every language for that matter, since we are dealing with different cultural backgrounds. After all, translation is nothing if not a transfer of cultural concepts.

*Click here for the detailed Powerpoint presentation and the complete bibliography of the study as presented at the 5th Meeting of Greek Translatologists.